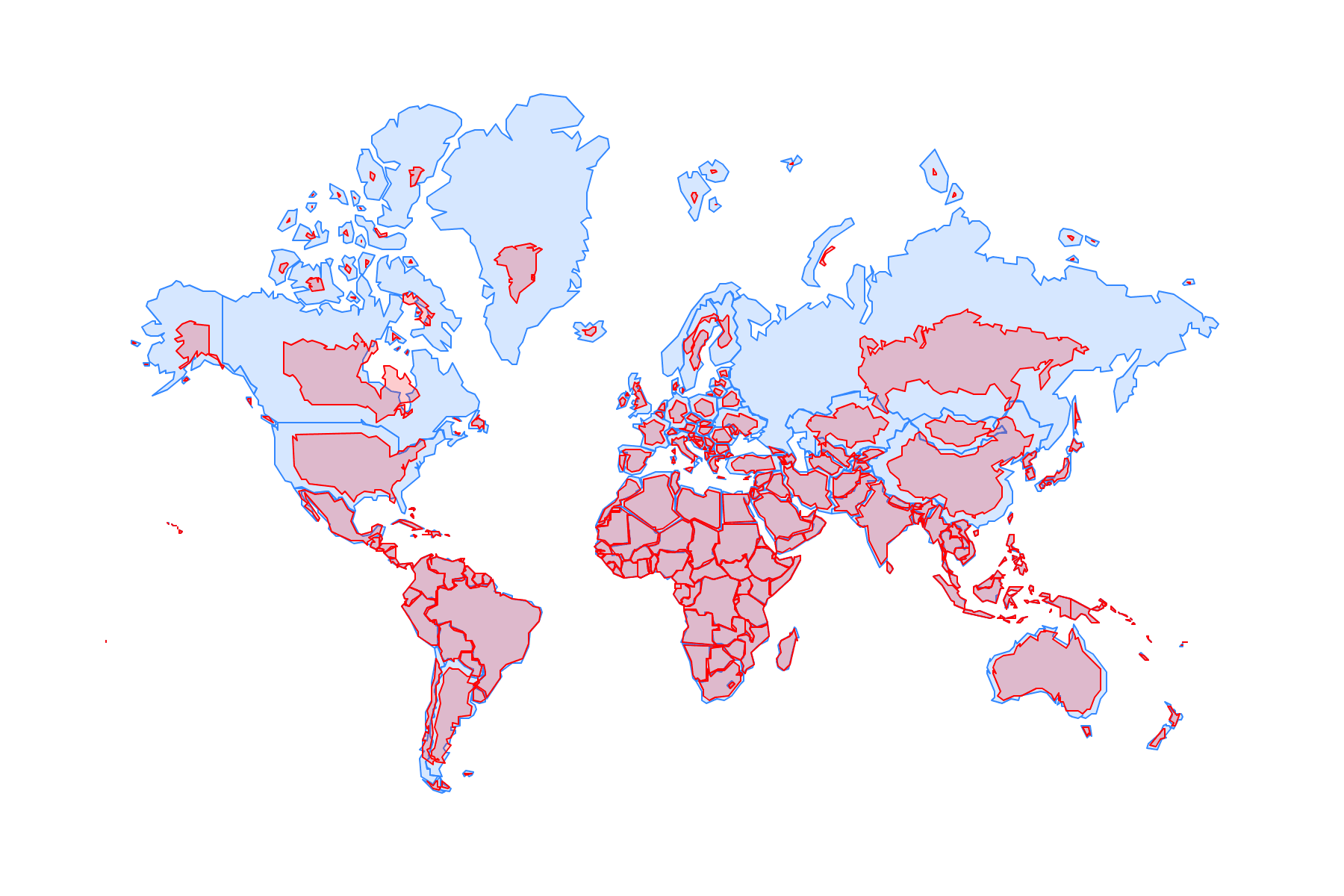

How much power lies in a map? The push to replace the ‘distorted’ Mercator projection with a more accurate map that portrays Africa’s truer size, has opened up a deeper conversation, not just about how Africa is drawn, but about how the continent is seen.

Conrad Onyango, bird story agency

As momentum builds on the campaign to adopt a “correct map” of Africa, older generations who were taught using the Mercator projection throughout their lives are voicing various views around the recent debate. For many, the map was simply part of the classroom furniture, a tool that defined their earliest understanding of the world. But later on in their professional lives, some began to question how the projection shaped the geography and identity of Africa.

Keith Claybrook, an Associate Professor of Africana Studies at California State University, Long Beach, in an interview with bird, recalled growing up, seeing and studying flat maps and globes. According to the professor, the size and location of the continents were taken for granted.

“Seeing distorted images often, presented as normal, and without the context of cartography, shapes one’s reality. The current map of Africa reduces its significance in the world while enhancing Europe and North America,” he said.

For Claybrook, the implications extend far beyond classroom geography lessons. He argues that representation on maps has a direct link to how nations and continents are valued on the global stage. Changing to a correct map, he said, demonstrates a commitment to truth and accuracy.

“In a world where ‘size matters’ and ‘bigger is better’, Africa’s correct scale enhances Africans’ presence in the world—including its historical, cultural, demographic, economic and political significance,” Claybrook explained.

Historical researcher, Marcus Boni N’Piénikoua Teiga had a similar early encounter with the Mercator projection. But, he only realised its implications much later.

“For a long time, Africans were taught this unreal map of Africa, and it has undoubtedly impacted their worldview,” he said.

Now, he views the campaign to correct the map as important for re-contextualising Africa’s place in history. However, in his view, it is not necessarily a silver bullet.

“Correcting it won’t automatically give us pride, because that must come from within, but it will restore Africa’s true scale,” said Teiga.

Not everyone sees the issue with the same urgency, with some experts remaining unconvinced that the distortion carries much weight in Africa’s larger struggles for opportunity and equity. South Africa-based urban planning expert Kathu Muruba, who admitted to never paying attention to what map was used during his early years, questioned whether cartography alone can address Africa’s deeper challenges.

“I don’t think changing it has any benefit if the same Africa is still not creating equal opportunity to jobs and education. Our economy is still a cat-and-mouse race,” said Muruba.

While recognising the distortions in the Mercator map, Nigeria-based geospatial scientist Emmanuel Avula argues that they were not intended as deception, but as trade-offs in map-making.

“A choice for any projection depends on needs, conditions, and circumstances. The Mercator preserves shape, even if it distorts size. Africans may choose to adopt other projections, but calling Mercator a lie misreads cartographic intent,” explained Avula.

The debate was stirred with the recent push to promote the Equal Earth projection, developed in 2018 as a fairer representation of land masses, by the African Union (AU) in August. The AU sees the shift as symbolic but also as a political gesture in line with its agenda of repositioning Africa in the global order.

“It might seem to be just a map, but in reality, it is not. The Mercator entrenches a false impression that Africa is marginal, despite being the world’s second-largest continent,” said African Union Commission Deputy Chair, Selma Malika Haddadi.

The Mercator was created in 1569 by a Flemish cartographer, Gerardus Mercator, with its projections still used in tech companies, institutions and schools to date. However, there have been signs of a change in the over-reliance on the Mercator map, with search engine giant Google's Google Maps replacing it with a 3D globe on its desktop version. While the change is yet to happen on the cell phone app, Desktop users can switch back to Mercator if they prefer.

The media organisation Africa No Filter and Speak Up Africa launched the #CorrectTheMap campaign to support the adoption of accurate, equitable map projections such as the Equal Earth Projection and make them more mainstream. The campaign has garnered more than 6,000 signatures on Change.org. Africa No Filter Executive Director, Moky Makura, describes the Mercator as ‘arguably the longest-running misinformation campaign in the world.’

“When Gerardus Mercator introduced it in 1569, Pope Pius V was in power – and there have been 52 popes since then,” she noted.

She is now calling on global publishers, software platforms and educational bodies like Google, Microsoft, Pearson, Oxford University Press, Collins and Canva to adopt Equal Earth on their textbooks, templates, slide decks, design platforms and classroom resources.

“If Equal Earth is the default in PowerPoint, Google Maps or Collins World Atlas, then teachers, students, journalists and policymakers everywhere will make the switch easily,” she said.

So far, Africa No Filter and Speak Up Africa have partnered with ESRI, the global market leader in geographic information systems (GIS) software, which helped them recommend the Equal Earth Projection. They have also reached out to National Geographic, one of the most influential publishers of maps in education and media, for a partnership. For Makura, changing the default is less about cartographic aesthetics and more about disrupting a global hierarchy encoded into everyday tools.

“Maps are not just geographic tools; they have been political weapons,” Makura said.

Speak Up Africa co-founder, Fara Ndiaye, is also lobbying for Equal Earth to become the classroom standard across Africa, in the hope that international institutions will follow suit.

“The Mercator affected Africans’ identity and pride, especially children who might encounter it early in school,” said Ndiaye.

Claybrook and Teiga also echoed Makura’s sentiments. They believe Africa needs all hands on deck to make the change happen.

“It becomes our responsibility and obligation to update the map. The significance of Africa’s physical presence increases with its true scale,” Claybrook said.

“Greater Africa will be built—or not built—from within. A corrected map may help reframe history, but it cannot substitute for deeper structural changes,” said Teiga.

bird story agency